If you’ve been following me the last few weeks, you’re aware that I teach four phases in resolving conflict: Preparation, Invitation, Exploration, and Collaboration. Last week I wrote about the first two phases and this week I want to explain the last two phases.

Phase III: Exploration-The Heart of Conflict Resolution

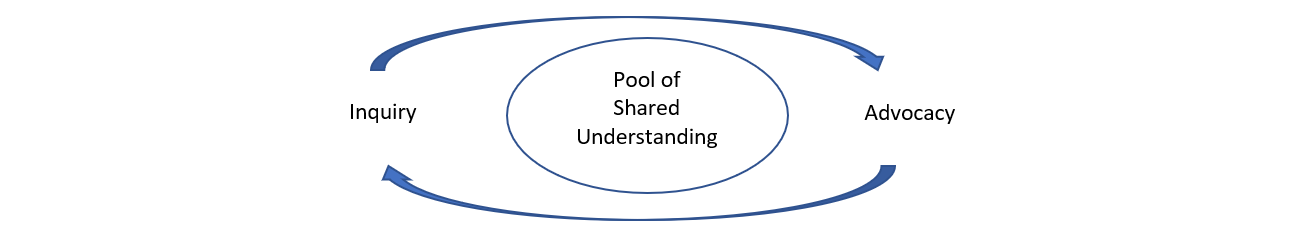

Exploration is exploring the viewpoint of each (or all) parties, not to solve the problem, which comes in the next phase, but to create a “pool of shared understanding.” This shared understanding is not agreement. It is getting all points of view on the table before you move to finding solutions.

The reason creating a pool of shared understanding is so important is that no one point of view represents the whole truth. All people bring diverse perspectives, biases, roles, needs, values, and backgrounds to the table, which set you up to arrive at different conclusions about the meaning of events. It’s through communication that you bridge these differences and develop a more complete understanding of what’s going on.

In fact, there is a good body of research which proves that our understanding and solutions are better the more points of view we take into account as we solve our problems. Afterall, two heads are better than one. Nobody is smarter than everybody. (See James Surowiecki’s best-selling book The Wisdom of Crowds as evidence of this point.)

The Skills of Inquiry and Advocacy

The exploration phase includes two major skills—inquiry and advocacy. Inquiry is encouraging others to disclose their point of view or inner experience and then listening with empathy. You inquire, by asking questions like: “How do you see things?” “What are your thoughts and/or feelings about what is going on?” Or even, “Help me understand how you arrived at your perceptions and assumptions?”

Advocacy is disclosing your point of view or inner experience. “This is the situation as I see it.” “These are my thoughts and/or feelings about what is going on.” “This is how I arrived at my perceptions and assumptions.” Then you end advocacy with inquiry, “How do you see it differently?”

You go back and forth and back and forth, balancing inquiry with advocacy and advocacy with inquiry until you come to a shared understanding of all points of view. This process is not linear. It’s not like you go around the room taking turns stating your point of view. You allow the conversation to evolve naturally, one person speaking at a time with others listening to understand his or her point of view, no one person dominating airtime.

This may go on for some time, until it seems like all viewpoints have been stated or have been added to the pool. If someone is leading the conversation he or she may ask, “Is there more anyone has to say? Are we missing anything? Is there anything that has been shared that anyone does not understand?”

The process looks like this:

When people learn this process, they sometimes object because they think it takes too much time. It is true that the process takes more time in the short run but also results in much improved relationships, better understanding of complex situations, and better solutions. It actually saves time in the long run by avoiding longstanding misunderstandings, unproductive conflict, and ongoing infighting.

Mistakes During Exploration

You can make two mistakes during the exploration phase. First is trying to persuade, convince, or coerce others into accepting your point of view. This sets them up to do the same and pretty soon you’re polarized around who’s right and who’s wrong which only creates resistance and power struggles. (“Tastes great!” “Less filling!”)

This also causes you to dichotomize, oversimplify and distort the truth. You want to win and so only pay attention to the data that supports your point of view and fail to pay attention to the complexities of a situation and valid points that others have to make.

The second mistake during exploration is moving too quickly into problem solving, the next phase of the process. It’s tempting to rush into looking for solutions to the problem before you have a really good understanding of the problem and everyone’s point of view. Not only does this result in people arguing for their own solutions but prevents you from getting enough information into the shared pool to come up with the best solutions.

So, let’s return to Ellen and George as an example of exploration. (Click here to read the first part of the story.)

Homecoming—Example of Phase III

Ellen approaches George, after a few days, to continue their conversation. “Hey, can we get back to talking about what it’s like when you come home from work? I’d still like to figure out how we can make this a better transition. I really want to hear what it’s like for you.”

(Ellen made a modified leveling statement by inviting George back into the conversation. She’s also transitioning to exploration by using the inquiry skill to invite him to talk about his experience.)

George opens up. “Sometimes, coming home is really hard. I’ve been working all day, had a lot of stress at work. In fact, I learned on Friday that I’d lost a big client I’d been counting on and I was really disappointed. And then I walked into a house which seemed like a disaster zone with messes everywhere and the kids whining and crying. It really got to me.”

(How easy for Ellen to react to George’s accusation. But she is clear that she wants to facilitate a productive discussion.)

“I wasn’t aware that you’d lost a big client. Do you need to talk about that?” asks Ellen.

George pauses, “Yeah I do. But not right now. Let’s figure this homecoming out.”

Ellen shows empathy. “So, between the disappointment of work and chaos of the house, last Friday night was really hard for you.”

“Yes,” says George. “I was really stressed and couldn’t handle it. I just needed space.”

“I get that,” replies Ellen. “It was pretty chaotic about the time you got home.”

George: “That’s right. It seems like it shouldn’t be so hard to have the house picked up and kids a little more pleasant since you were at home all day.”

(Again, it would be easy for Ellen to hear George’s comment as an accusation and either retreat or throw a counter-punch. But her goal is to have an honest conversation. Although his last statement didn’t feel good, she recognized it as an honest perception on his part.)

Ellen pauses, briefly, and then continues, “And I want to make your homecoming and our evenings better, less frustrating for both of us.” She goes on. “Can I share what it’s like for me about the time you come home?” (Transition from inquiry to advocacy.)

“Okay.” (George is softening. Ellen has been willing to listen and not provoke him to battle.)

“Late afternoon is the hardest time of the day for me and the kids. We’ve been together all day and I’m feeling pretty worn out and the kids are getting hungry and on edge. Sometimes when you walk in the door, I want to throw my hands up and say, ‘Your turn. I need a break.’”

“I get that. Have you thought of structuring your day so you aren’t so tired by the time I come home?”

(It’s common for someone to jump to solutions or offer “quick fixes” during exploration. They usually come too soon, before we have all the data in the pool of shared understanding before moving to this phase. This is a judgment call by Ellen, since she is guiding the conversation.)

“You know, I’m sure there are some things I could do differently and I want to explore that. But, first, I need to get something else in the open. Can I share with you the hardest part of Friday night for me?”

“Okay.”

“You made some kind of comment like, ‘I’m not a good enough mother because I can’t control my kids.’ I felt really hurt and unappreciated. I wanted to shut down and not talk to you the rest of the night. It was hard for me to be around you.”

“Oh yeah. I forgot I said something. Sorry. I guess it was my frustration speaking.”

“Well, it hurt. I don’t want to hold onto it, but need you to know that it really bothered me.”

The dialogue may continue as Ellen and George build a pool of shared understanding by gaining insights into one another’s perspectives and feelings. Such conversations may take lots of twists and turns depending on the history, depth of feelings, and perceptions of both parties. On the other hand, they may be ready to enter into collaboration, the final phase of conflict resolution.

One final thought. If all parties understand the steps of dialogue then the process is usually easier. But often, one person is more aware and likely to steer the conversation. In this case, it is Ellen. She has the greater responsibility to listen deeply, find the right balance between inquiry and advocacy, and keep the conversation on track. Over time, both can learn the process and share this responsibility.

Phase IV: Collaboration

We’re now in the final phase of conflict resolution—collaboration. This is like coming full circle since collaboration is the name of one of the styles of communication. The entire dialogue process ends in the phase of collaboration.

As this word implies, we’re now working together to come up with and implement solutions and actions that all parties can agree upon. Hopefully, at this point, we aren’t pitted against each other or competing to have our way but feel like we’re members of the same team working together to find the best solution. We’ve gotten here by establishing trust and goodwill and by creating a pool of shared understanding. During collaboration, we translate our goodwill and shared understanding into tangible solutions and actions.

Three Steps of Collaboration

There are three steps in achieving solutions during collaboration. Step one is to identify the needs or what is important to each party in order to come up with a good solution. Unmet needs are often at the heart of conflict. And rather than being aware and expressing our needs directly, we’ve learned to send blaming and judgmental messages. For example, a husband says, “You spend so much time at work. I’m beginning to think you love your work more than you love me.” His hurt and blaming message is really expressing an unmet need for intimacy or connection.

Or an employee of one department says, “Those people in sales are bozos. They make promises to customers without having a clue about what it takes to build a good product.” Again, this judgmental message covers up a deeper need someone has to feel respected and/or engage in more open sharing of information. Understanding the needs behind such statements helps us avoid overreacting so we can search for solutions that meet the needs of all parties.

So, this step is not yet looking for a solution, but finding out what is really important to people. By identifying what is important, you give yourself the flexibility to explore various solutions that can meet all needs and avoid getting locked into power struggles. Your needs and deeper concerns, therefore, become the criteria against which to compare possible solutions.

Now let me say that needs may have already been expressed during the exploration phase of dialogue. They may have been stated as part of building a pool of shared understanding. However, you still raise the question and make what is important explicit during collaboration by asking questions that invite people to share their needs. You do this by asking such questions as, “What is most important to you as we search for a solution?” Or, “What needs do you have that need to be met for you to know that we’ve solved this problem?” You then get these needs out in the open.

Here’s a simple example. It’s Friday evening and a couple is experiencing conflict about what to do this evening. She wants to go to dinner and a movie and he wants to watch a program on tv. As long as they argue about solutions, they’re likely to remain stuck or eventually set up a win/lose situation. However, if they can identify their deeper needs, they can choose from a wider selection of options and have a better chance of finding a solution that meets both their needs.

So, she may ask, “What is most important to you tonight?” He may say, “It has been a hectic week for me and I want to relax and not have to interact with other people.” She may then share, “What is important to me is time together and to be away from responsibility for kids.” These needs are deeper than going to a movie or watching tv. By understanding one another’s needs, this couple can be more flexible as they brainstorm various solutions that may work for both of them.

If we’re talking about two departments, engineering and sales, pitted against each other and invite each to share what is most important to them, we might hear sales say, “It is important that we give our customers answers right away about when they can expect the product.” Or, “It’s important to us that we consistently meet production deadlines.” Perhaps engineering would say, “It is important to us to have a process that captures all customer requirements up front.” Or, “It is important that all departments involved agree on the process and steps required to produce deliverable.”

Of course, this example is hypothetical and the list of what is important may be longer than these few items. But I hope you’re getting an understanding of the kinds of ideas people will come up with as they identify their needs or what is important to them. The take-away is that you want to be sure that you’ve given each party the opportunity to make their needs, or what is important to them, explicit as you move into searching for solutions.

Step Two

The second step is brainstorming alternatives. You’re not yet at the solution or action stage. You’re looking at options, as many as possible, before you settle on a solution. The idea here is to be flexible, think outside the box, and get as many possibilities out in the open as possible before settling on solutions. You do this by brainstorming.

Here are some rules for brainstorming:

- Make sure that everyone understands your objective in generating options.

- Each person shares ideas, round robin or spontaneously.

- One thought is expressed at a time.

- No criticism of any ideas.

- Outrageous ideas are encouraged.

- No discussion of ideas except to clarify its meaning.

- Build on other’s ideas.

In my example about a husband and wife trying to decide what to do on a Friday night, they want to be creative in coming up with options: Hire a babysitter. Take some alone time before doing something together. Go for a walk. Spend time in a park. Go to a quiet restaurant for dinner or desert. Go to a movie if we don’t have to drive far. Watch a movie we both love on tv. And so on. They aren’t trying to push one idea on the other, just coming up with various options.

Not all of these options are going to be equally appealing to both people. That’s okay. You’re not judging them at this point, just generating your list.

Step Three

Now you’re ready to move to step three which is coming up with actions or solutions. By now people are feeling heard and understood. They have identified what is important to them and brainstormed options. Now you want to look at these options and select those that will best meet everyone’s needs. This is called consensus and usually involves finding solutions that are more expansive than any one individual would have selected, and yet are in the best interest of everyone involved.

For example, the husband and wife deciding what to do on a Friday evening may come up with the following solutions. Husband takes 30 minutes of quiet time before joining the family. They find a neighbor boy who can run over and watch the kids as they go for a quiet walk in a park. They return home after the kids are in bed and watch a movie on Netflicks.

Although not as powerful as consensus, compromise is another way of resolving conflicts when issues are particularly complex or parties to a resolution are so divided that they are not able to work a conflict through to consensus. Compromise involves give and take. You give something of importance to another person to get something important to you. I certainly don’t recommend it, particularly in your personal relationships. You build so much more unity and goodwill when you are able to arrive at consensus.

Of course, this process of coming to agreement happens much more easily and spontaneously when we have used the other skills of dialogue earlier in the process. Problems arise when we attempt to impose our solutions on others. But when we take time to listen and allow everyone to talk about their needs or what is most important to them, the buy-in to our solutions is very high.

Homecoming—Example of Phase IV

George and Ellen have a much better understanding of one another’s point of view and are now ready to search for actions that can help make their evenings, particularly transition home for George, go more smoothly.

George identifies his needs: knowledge of evening schedule; some quiet time before interacting with family; orderly house; fun, not stress, with kids; More structure with kids during evenings and dinner.

Ellen identifies her needs: Compassion, not judgment; a warm greeting; help with kids; time for us to connect and talk; time away from family, excluding work.

They then brainstorm various options to meet these needs:

- Talk at beginning of day about schedule and plan for evening

- Have a consistent dinner time

- Both help with dinner

- Who doesn’t help get dinner, if not both, does cleanup

- 10-minutes to clean up clutter before George comes home

- Spouse not getting dinner will interact with kids

- Ellen to get some time away one night a week

- 15 minutes of quiet time after arriving home

- 15 minutes of quiet time after dinner

- Connection time later in evening

- Speak respectfully even when frustrated

- Get more training in parenting to create a more peaceful home

Finally, Ellen and George review their list of options and select those that they can both support:

- Talk at beginning of day (or preceding night) about schedule and plan for evening

- Have a consistent dinner time—6:30 pm most days

- Spouse who doesn’t get dinner does cleanup

- George gets 15 minutes of quiet time after arriving home

- Ellen gets some time away one night a week

- Ten minutes of talk-time later in evening

- Read book on parenting together and agree on structure/expectations during dinner

Once they had listened to one another and built a pool of shared understanding, George and Ellen were ready to decide on actions to make the situation better. They did so by making what was important to each of them explicit, brainstorming options, and coming up with actions they could both support. Certainly, their final plan was different than either would have come up with on their own; different but also better since they made the plan together. The final part of collaboration is to talk about how it’s going periodically, and make adjustments as necessary.

Of course, this process of coming to agreement happens much more easily and spontaneously when you have used the other skills of dialogue earlier in the process. Problems arise when you attempt to impose your solutions on others. But when you take time to listen and allow everyone to talk about their needs or what is most important to them, the unity in a relationship and buy-in to solutions is very high.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, we have become so tribal and polarized in our societies today that the ability to talk openly and work together to solve our common problems is becoming a lost art. The consequences are severe and far-reaching. And although you may feel little control over what happens on a large national, international or even corporate scale, you can influence what happens in your primary relationships, within your homes and with those with whom you work and associate daily.

Ronald Reagan once said, “Peace is not the absence of conflict, it is the ability to handle conflict by peaceful means.” My hope is that this article has helped you learn some principles and skills so you can step up to conflict with the intent to understand each person’s point of view in order to learn and grow together.

So, remember the phases and steps of dialogue. Phase I is preparation by putting yourself in the mental state to step up to conflict in a helpful way. Phase II is invitation in which you lay the ground work and make it safe for another person to enter into dialogue with you. Phase III is exploration in which you build a pool of shared understanding by getting all points of view out on the table before you attempt to resolve your differences. And Phase IV is collaboration in which you work together to come up with solutions which all of us can support.

Your next step is to practice, and practice, and continue practicing. The good news is that life gives you lots of opportunity to practice resolving conflict. And as you practice, you’ll get better and better. In fact, the only way to get better is to practice. And I want you to know that the very word practice implies that you will make mistakes. Sometimes you’ll handle situations really well, sometimes fairly well and sometimes you’ll blow it. Please make that okay. As I’ve said before, you’ll get do-overs, if you’re willing to keep learning and growing.

Stepping up to conflict is not easy. So many people opt to avoid it altogether or to treat the other party as an enemy that must be defeated. In truth it takes humility, responsibility, courage, goodwill, and emotional maturity to work through conflicts to a productive end. May you be willing to face and work through the conflicts of your life.

Click here to become a master at resolving conflict.